Issue No. 16: Three Aspects of My Compositional Process

During the past two decades, I have composed over sixty pieces (and several more during my youth that I later removed from my works list). In that time, I have definitely cultivated a compositional process that works for me. I absolutely concede that everyone composes differently but in this issue of The Theisen Journal I share three aspects of my compositional practice that I believe lead to positive results.

I am curious if you do something similar, would like to try my approach at some point, or completely disagree! After reading, share your thoughts via comment or DM on social media.

Without further delay, here we go. Read on!

Aspect #1: The Power of Openings

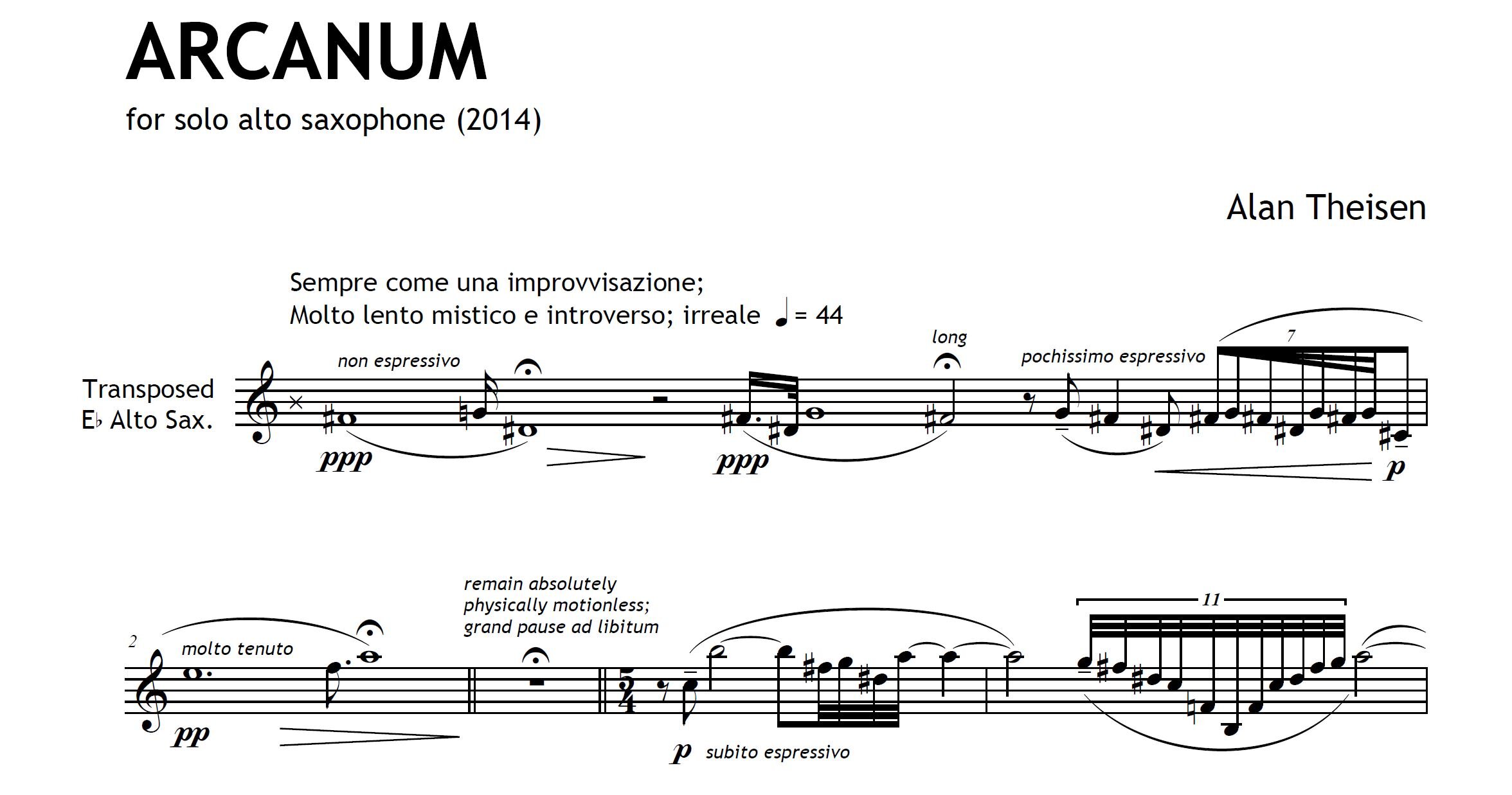

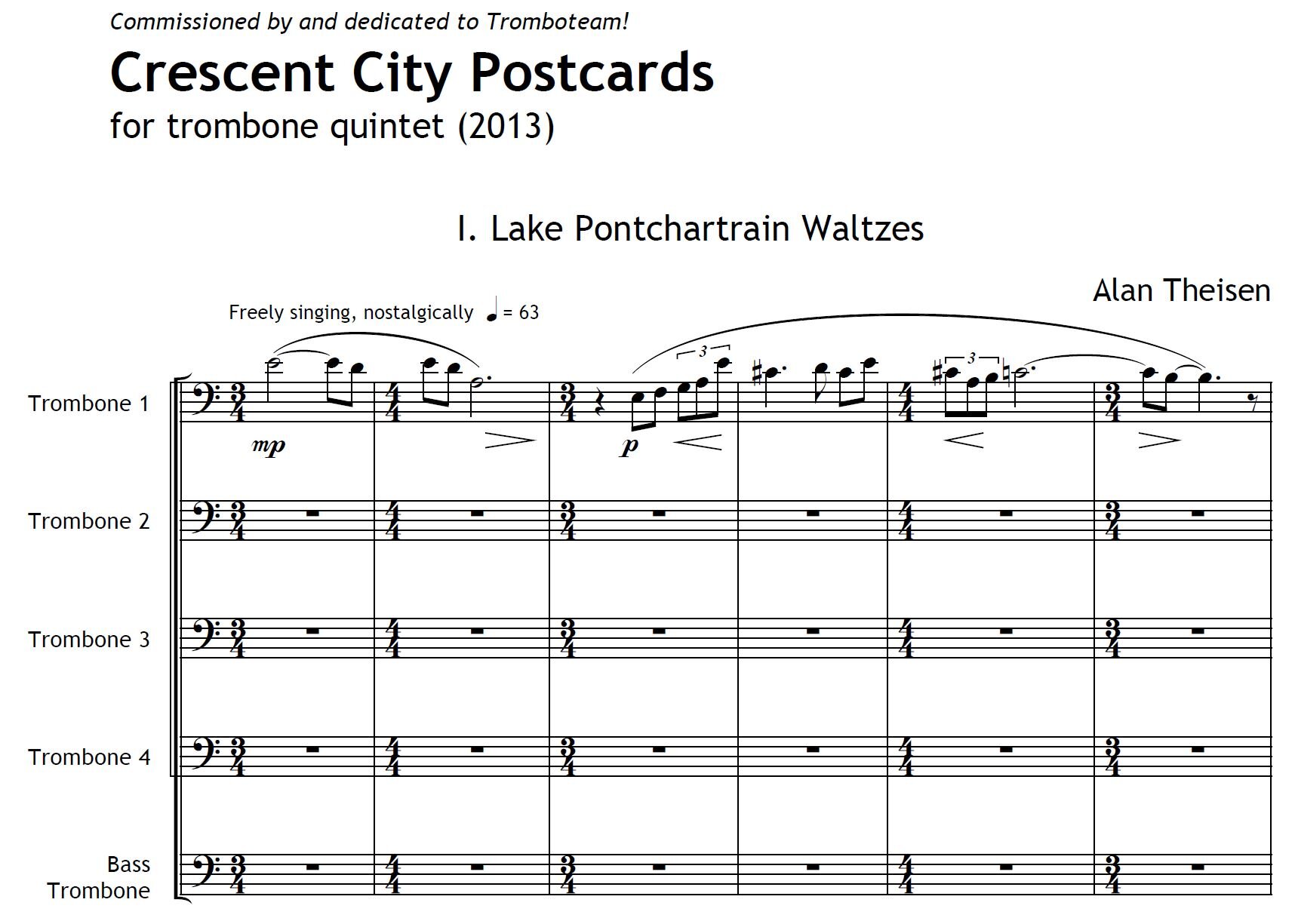

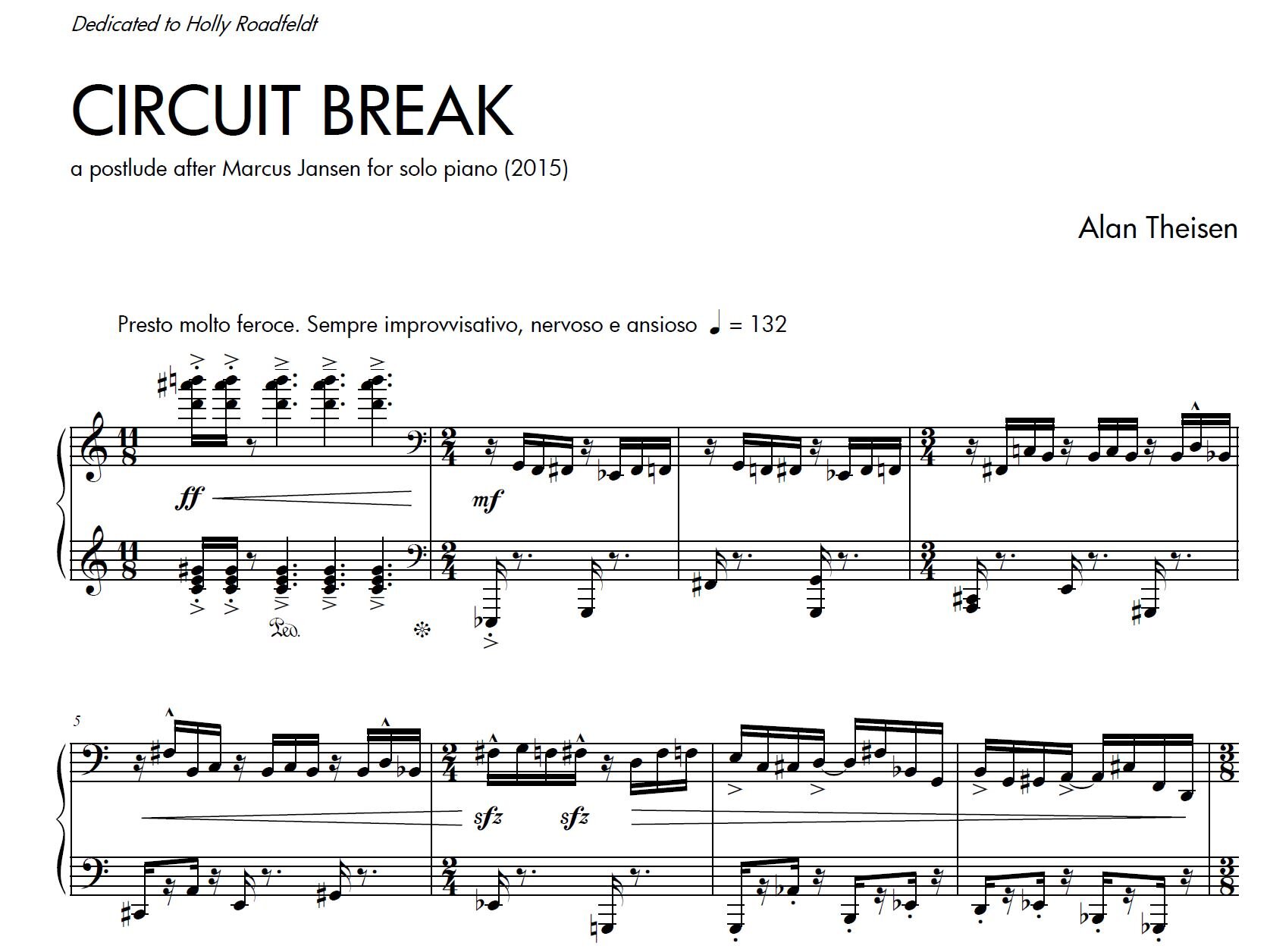

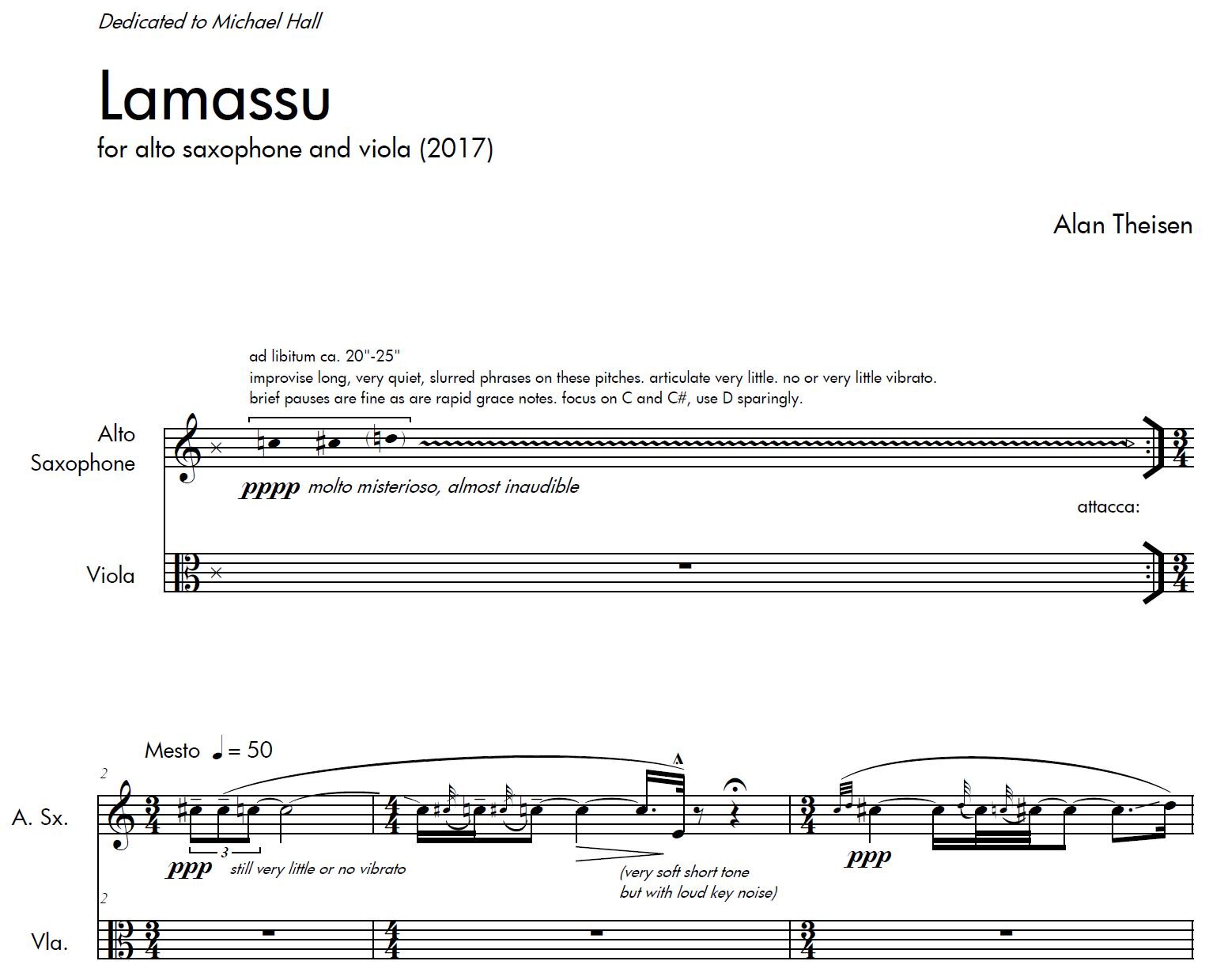

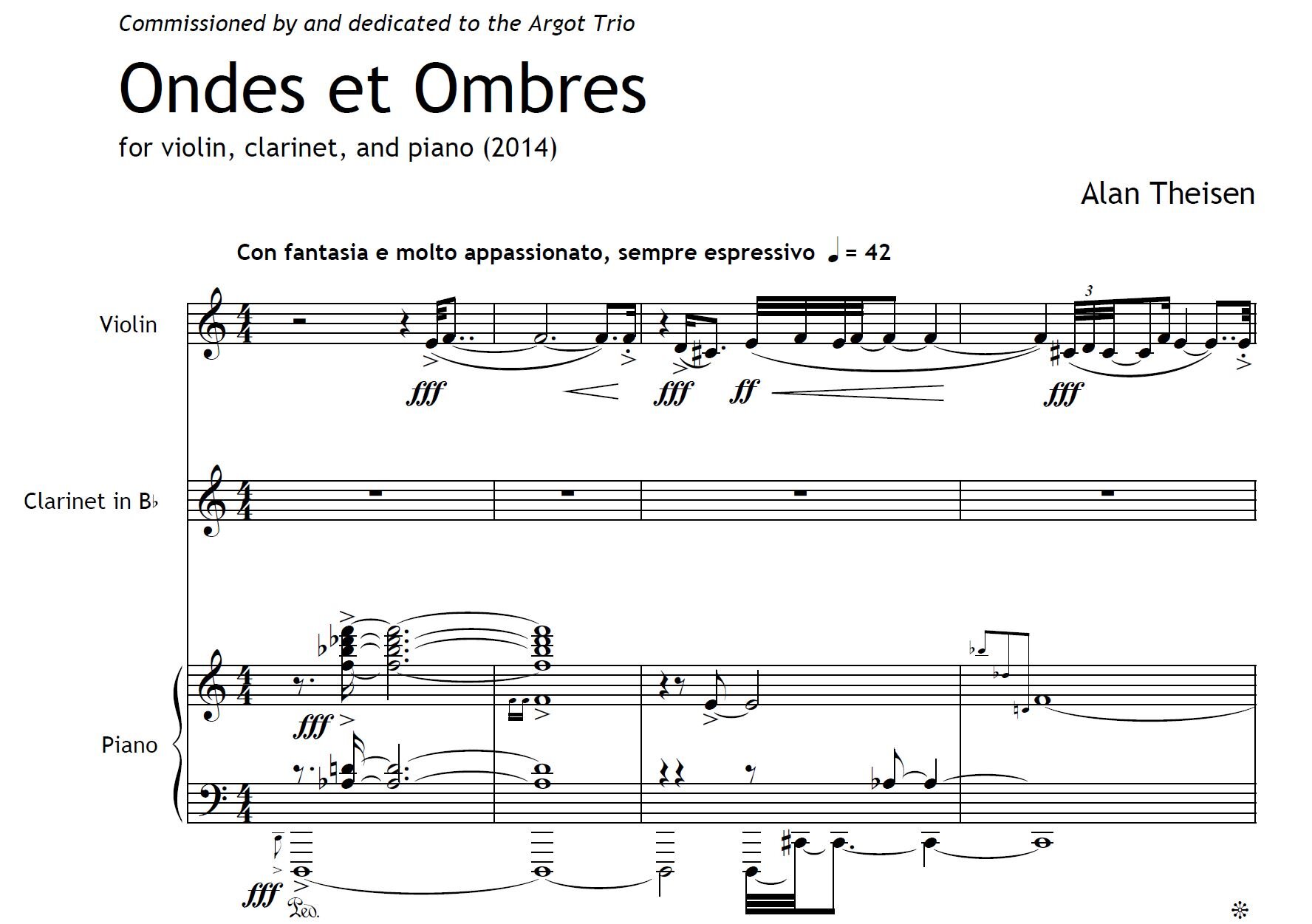

I love openings. I soak them up. I memorize them. Not only those from pieces of music but from films, poems, novels, historical battles, essays, plays, musicals, and so on. I am fascinated by how creative individuals “break the ice” with their audiences.

Openings are powerful - more powerful than sometimes we care to acknowledge.

I believe that the first measures of a composition provide a universe of information to listeners that is immediately absorbed no matter the familiarity level of the audience; these initial sounds become (whether we as composers want them to or not) an integral part of the referential framework created by the listener within which they will 1) critically assess the work and 2) explore a variety of meanings - internal and intertextual, intended or accidental, logical or intuitive.

That’s why personally (I know there are other viable methods) I always begin writing a piece with the first few measures. I cannot seem to do it any other way. I must hear those crucial embryonic gestures before the rest of the composition will unfold in my brain.

When I am commissioned to write a new piece, I close my eyes and envision the performers on stage. I am in the audience. I see the title of the piece and my name on the program. The lights dim. The baton goes up and/or the first breath is taken, then… what? What is the first sound I hear the performers making?

Unlocking this mystery is almost without fail my first step in creating a composition.

Aspect #2: Have A Plan

Once I have the opening more or less in place, I then draft a form diagram for the remainder of the movement or composition. I liken this to a contractor not starting construction without having blueprints nor knowing what type of building was to be constructed. Yes I may certainly change my mind as I go along, but I’m not going in without a plan!

Below is my original early pre-compositional form diagram for the opening movement of my Symphony No. 2. At this point, I literally only had the downbeat fortissimo “stinger” chord of the piece. On the top and bottom systems you can see harmonic/motivic sketches, a tone-row, possible timpani pitches, and melodic possibilities. The second (middle) system is what I really wish you to focus on. I have very little specific pitch, rhythmic, or metric information down. It is more of a doodle of energy waves, proportions, orchestration, contours, textures, and gestures.

Furthermore, no matter how long the movement - three minutes or twenty minutes - I put the entire form diagram on a single line/staff of a single 18” by 12” piece of paper! I want to see my goal in one glance.

For the record, my Symphony No. 2 first movement ended up very close to this original sketch.

Early “blueprint” form sketch of Symphony No. 2 for clarinet, trombone, and wind ensemble (2017).

Aspect #3: Know the End Before You Get There

I usually compose “from left to right.” In other words, I write as the piece will unfold in time as it is performed. This helps me gauge the impact of various formal events on the audience.

The most notable exception to this is that when I make it about 70% way through, I will skip ahead and compose the closing measures of the work. The 70% mark is about the time when two things happen: 1) I can imagine where all of this is going and whether or not my original form diagram sketch will succeed and 2) self-doubt begins to creep in regarding the merits of the piece at hand.

Knowing how the piece will end helps me push through the wave of “oh my god this is all total crap” feelings that might pop up.

Then all I have to do is retroactively compose the music that goes from the 70% mark to the 98% point and I am done! Double bar!

I really enjoy this strategy of working backward from the desired result. Chess Grandmaster Josh Waitzkin learned much during his schooling by manipulating various endgame scenarios and reverse engineering the bulk of the game that would result (in contrast to the traditional approach of memorizing thousands of opening gambits and hoping they played out as desired against real-life opponents).

As always, let me know your thoughts via comments or DM. Thanks for reading and keep creating!